For some time, Worthing’s been singing to the tune of one local property developer. Roffey Homes are behind a number of developments in the town.

Established in 1960 as a building company, it’s since 2000 that the company has taken off; all the directors are members of the Cheal family, and presumably the change in direction came when the children took over their father’s business. All Roffey Homes work is carried out by Westbrooke Developments – registered at the same address and with the same set of company directors.

Everything Roffey Homes build is billed as ‘iconic’ but in fact, they’re all pretty bland regeneration-lite architecture. It’s all blocky, all crams as many ‘luxury flats’ into as small a site as possible, all degrades the public realm with poor integration with the street, and is all aimed not at local people who need homes, but at people who wanted a second home by the sea, or somewhere to commute from. In short; they’re not developments that are good for Worthing’s people.

They’re not the kind of buildings that are recognised as good planning anywhere (Jacobs, Mumford and Tibbalds are all turning in their graves), but in a town that’s been desperate for change (pre-Roffey, there have been no significant developments since the 1970s) and which has a large incoming population who don’t understand the grain of the town’s history, they’re big shiny signs that change is happening. Council officers can point and them and say ‘we’re delivering regeneration’ and councillors can say; ‘look what was built on my watch!’ It’s a great example of the Politician’s Syllogism:

We must do something, this is something, we must do this.

But actually the ‘something’ is doing huge damage, although it’ll probably be 20 years before the scale of that is understood. Remember that the Guildbourne Centre, and the Marks & Spencer site on the seafront, and even the old Aquarena were all seen as high-quality when they were built.

The first major Roffey development destroyed a lovely 1930s block, Roberts Marine Mansions. This building belonged to one of London’s trade guilds, and provided homes for retired tailors and haberdashers. It was built with care and class, full of beautiful period details, windows and railings and reliefs on the walls, and was knocked down in the late 1990s to build a pastiche Art Deco block where apartments sell for twice the local average home and 17 times the average local wage.

That’s a pattern they’ve continued on the site of the Warnes Hotel, Eardley Hotel and Beach Hotel, all landmark buildings demolished to build cheap pastiches full of luxury apartments.

And those three developments do further damage, removing any hopes of tourism growth in Worthing at a time when UK tourism is in growth. A recent report suggested that demand for affordable hotel and guesthouse accommodation is high, and the existing businesses turn away trade, and that there’s a local need for an ‘incremental growth in accommodation supply and a focus on high quality, modern accommodation offers that can generate new business.’ It says that Premier Inn are looking for an 80 rooms site locally, and there’s further potential to develop the market for accommodation from kite surfers and watersports markets.

Even worse is the way that the developments are segregated from the town. The Warnes site and the neighbouring Eardley development are both at key points on Worthing seafront, providing the link between the town centre and pier, and the revamped East Beach, fast becoming the new centre of beach life in the town. But both developments are walled off, providing aggressive frontages and contributing nothing to the street. The Warnes building (pictured above) has a wall at street level. Neither building has entrances or windows at street level. They’re very carefully excluded from public life, and not for local people.

That goes against the successful regeneration of this area of Worthing, too, which has all been about fine grain, people-scaled urbanism. The success of Craft:Pegg’s public realm at Splash Point (pictured below), the East Beach Studios, even the new swimming pool itself, are because of their friendly scale.

And incredibly – Roffey Homes latest plan is even worse. Worthing Borough Council spent over £17 million building a new swimming pool, to replace the larger 1960s Aquarena. To give you something to compare that to, it’s the same cost as Margate’s Turner Contemporary, which has attracted over 1.5 million visitors to the town and has generated acres of press coverage. To fund this expensive new pool, with a pirate ship inside named after local councillor Paul Yallop, the old Aquarena site would be sold for development. It’s a prime beachfront site, at the edge of Worthing’s string of Victorian parks and butting up against the new swimming pool’s expensive (and genuinely iconic) architecture.

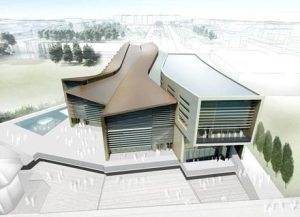

Roffey’s proposal for this important spot? a twenty storey towerblock (taller than any other building in Worthing) providing more exclusive apartments. It’s clad in something white, has a poor rhythm of jumbled windows, and has a string of cheap balconies up the sea side, A cluttered jumble of low rise blocks and some privatised public space at the bottom complete the proposals. Is it good? No. It’s cheap architecture, it doesn’t relate in any way to the location, it contributes little to the expected future of this active beach and it crams homes into a small site, straining local infrastructure. Schools locally are full, the small grid of local roads often at gridlock and the next door pool often has long queues.

Residents already expressed their concerns, at a series of consultations in June; but the developers have ignored them and come back with a towerblock the same size.

And it’ll probably get permission, because Worthing Borough Council need to pay down their large debts on the neighbouring pool. Councillor Bryan Turner, in charge of regeneration, said before any plans were even drawn up that “I look forward to working with Roffey Homes, to bring another high quality development to Worthing.” When you have the council’s Cabinet Member as your cheerleader, you must feel pretty confident.