Tag: playful

TribevTribe

Five tribes will fight across Margate for the next month. TribevTribe is a month-long artwork which takes the centre of Margate as a board to play on.

When players choose to play they collect a Game Card, which randomly assigns them to one of five Tribes – Mods, Rockers, Punks, Hippies and Ravers. So if up to five people decide to play together, they’ll be playing for different teams.

Players visit venues across Margate, looking for a hidden Dead Letter Box. Usually taking the form of a wooden box, the Dead Letter Box is identified by some combination of the five Tribe symbols. Players can visit each venue once a week. In a few places, the Dead Letter Box is held by staff, and there’s a password to access it; the clue to these stashes can be found in other Dead Letter Boxes.

Every Dead Letter Box contains two things for sure; a Log Book and a pack of Chance cards. Players record that they’ve visited to score a point, and take a Chance card which can send them to other venues or set them another task to score more points. Dead Letter Boxes might also contain rewards or gifts left by other players. These might change week to week, and special rewards might be announced via social media.

Every Dead Letter Box contains two things for sure; a Log Book and a pack of Chance cards. Players record that they’ve visited to score a point, and take a Chance card which can send them to other venues or set them another task to score more points. Dead Letter Boxes might also contain rewards or gifts left by other players. These might change week to week, and special rewards might be announced via social media.

Players can play by themselves, in secret; they can just visit each venue, find the Dead Letter Box and record their visit. The game is like a less technological version of geocaching. It’s a good way to explore Margate.

Or players can choose to play TribevTribe on a more social level. Players don’t know who else is on their team, but can accept Chance card challenges to use social media to meet other players.

Or they can, by gathering strangers together (and without even meeting them) play strategically, agreeing to all visit certain venues in an attempt to conquer them.

That’s important because scores are collected from the Dead Letter Boxes, and announced on a rolling basis. Each week, it will be announced which Tribe has scored most points and conquered each venue, encouraging the other teams to try to retake those places on the board.

Around twenty venues are involved in the work. Each venue can choose how to participate; the simplest way is just to host a Dead Letter Box. But some venues have chosen to get their staff playing, to add extra levels of content, or to champion one of the five Tribes on social media. The first fifteen venues are already in play – and more will be added next week. The venues are large, big public funded attractions like Turner Contemporary, and small, independent shops, cafes and attractions like The Shell Grotto, Rat Race and Proper Coffee.

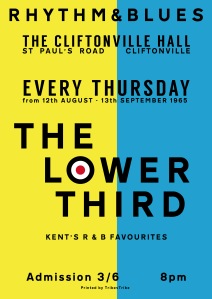

Other venues are involved in another way. The game’s skin of subcultures has led to the creation of a series of posters referencing real gigs and events from Margate’s past; a residency in a community hall for The Lower Third, a Hawkwind community benefit, a wrestling match and so on. These post for long-gone gigs can be found displayed around the town, and players score extra points for finding them, too.

Other venues are involved in another way. The game’s skin of subcultures has led to the creation of a series of posters referencing real gigs and events from Margate’s past; a residency in a community hall for The Lower Third, a Hawkwind community benefit, a wrestling match and so on. These post for long-gone gigs can be found displayed around the town, and players score extra points for finding them, too.

The game is designed to scale, flex and adapt as it happens; ‘it’s iterative design’, a Design Council expert said as she took her Game Card.

TribevTribe was conceived after carrying out evaluation of last year’s Summer of Colour, a festival organised by Turner Contemporary. That evaluation found that people’s movement across Margate from venue to venue was limited. And that people weren’t generally attending multiple events within the festival.

TribevTribe aims to address that, by giving people an incentive to move between places. But it also creates a linking structure for the diverse venues within the festival, and connects them to smaller independent shops, cafes and attractions across the town.

Playing out isn’t about rules

I’ve been helping one of our neighbours take part in a scheme run by the local council called Playing Out.

I’ve been helping one of our neighbours take part in a scheme run by the local council called Playing Out.

The idea is a good one – to encourage more people to play outside with their children. It’s pro-community, pro-family, pro-child. It brings animation back to streets. What’s not to like?

Hi-visibility jackets and whistles, that’s what.

Where we live, children play in the street. They scooter, and they cycle. They sit on the path and play with Lego. They chalk on the walls and the pavements. They chase each other with Nerf guns. They pop into each other’s houses to collect toys or a glass of water. Parents sit or stand outside and gossip, or sometimes stay upstairs and watch from a window, or often get on with jobs like gardening or polishing the car. Car drivers slow down when they see children around. This street isn’t a miracle; it’s simply down to us, the parents in our street, doing it. Investing time and effort. Our children have been taught to ride bikes early, encouraged to knock for friends, and shown the boundaries, invisible lines at each end of the road. We’re like Jane Jacobs‘ best dream, a mixed-use street right in a town centre, with the eyes of watchful parents on the street, and an increase in social capital as a result of scooters, bikes and chalk.

With Playing Out, though, the rules are different. The road is officially closed to traffic. Neighbours form a steering group and meet to discuss the idea. Leaflets (there’s a template, set wording) are stuffed through letterboxes. There are official signs up, and stewards have to wear high visibility jackets and carry whistles. Car drivers aren’t allowed in, unless they’re residents and they’re walked in behind a steward. You must discourage children from neighbouring streets from joining in – it’s just for your children. It’s closing down the street, rather than opening it up.

With Playing Out, though, the rules are different. The road is officially closed to traffic. Neighbours form a steering group and meet to discuss the idea. Leaflets (there’s a template, set wording) are stuffed through letterboxes. There are official signs up, and stewards have to wear high visibility jackets and carry whistles. Car drivers aren’t allowed in, unless they’re residents and they’re walked in behind a steward. You must discourage children from neighbouring streets from joining in – it’s just for your children. It’s closing down the street, rather than opening it up.

It’s great that with a Playing Out scheme, children get a few hours to really run free. And of course, in some streets this is the only way to make it happen.

Used creatively, it’s a great opportunity. Our first event went much further than the official guidelines allow, with our neighbourhood coffee shop rolling up on their Vespa mule to give us a decent drink, one neighbour setting up a cake stall for charity, and my sound system in the front garden to give us a ska and calypso soundtrack. None of this took any extra organising. There were no committee meetings or minutes. A few of us had hi-vis jackets to hand, and put them on when they were needed. We ended up with a street festival, a sunny afternoon with all the neighbours and their friends outside. People passing through our street, a busy route for schools and shops, stopped and joined in. Our children met other children in the street, and made new friends. It worked.

But that’s because we bent the council’s rules, went a bit further, opened up the box of Playing Out possibilities. We’d previously held a very similar street party with no official road closure order, just asking people to not drive down our road for a couple of hours. It’s possible. It’s easy. So we took Playing Out and made it fit our street.

It’s not to say that Playing Out is a duff idea. Far from it – anything that challenges the car-is-king orthodoxy is good. But if you want people to look after their streets, create their own community, really come together – then you have to accept that they will do that in their own way. That might mean they don’t have meetings, or that they design their own leaflets, or that they find a different model of managing events that works for where they live. If you give people freedom, you have to trust them. If you want local, it will be distinct. If you want people to reclaim the streets, you can’t complain when they do.

It’s not to say that Playing Out is a duff idea. Far from it – anything that challenges the car-is-king orthodoxy is good. But if you want people to look after their streets, create their own community, really come together – then you have to accept that they will do that in their own way. That might mean they don’t have meetings, or that they design their own leaflets, or that they find a different model of managing events that works for where they live. If you give people freedom, you have to trust them. If you want local, it will be distinct. If you want people to reclaim the streets, you can’t complain when they do.

Replacing one set model of street use with another, as equally rigid and defined, isn’t the answer. We should be creating streets where play spills out and is spontaneous, streets that are a little chaotic and full of life, streets where people regularly bump up against each other in unexpected ways, streets where people find their own ways to make it work.

Streets, to paraphrase Jane Jacobs, which can provide something for everybody because they are created by everybody.