Here’s some of 2014’s design work for Margate’s The Black Cat.

These are four club night Face Up!, a celebration of Margate’s place in the history of youth culture:

These are for funk night Watermelon:

Here’s some of 2014’s design work for Margate’s The Black Cat.

These are four club night Face Up!, a celebration of Margate’s place in the history of youth culture:

These are for funk night Watermelon:

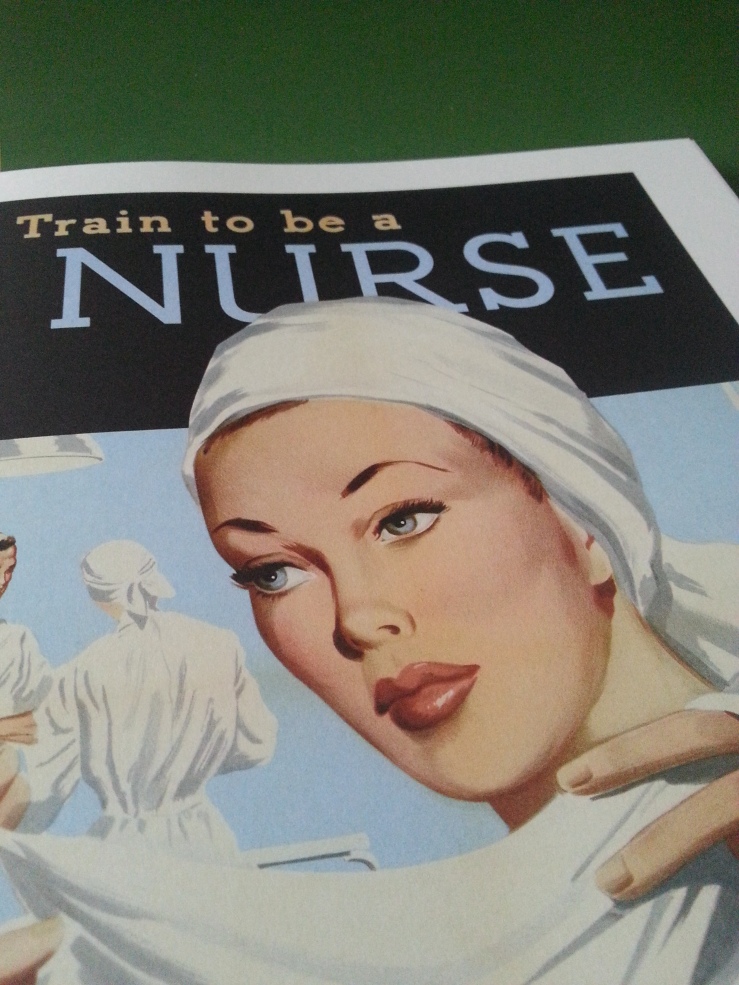

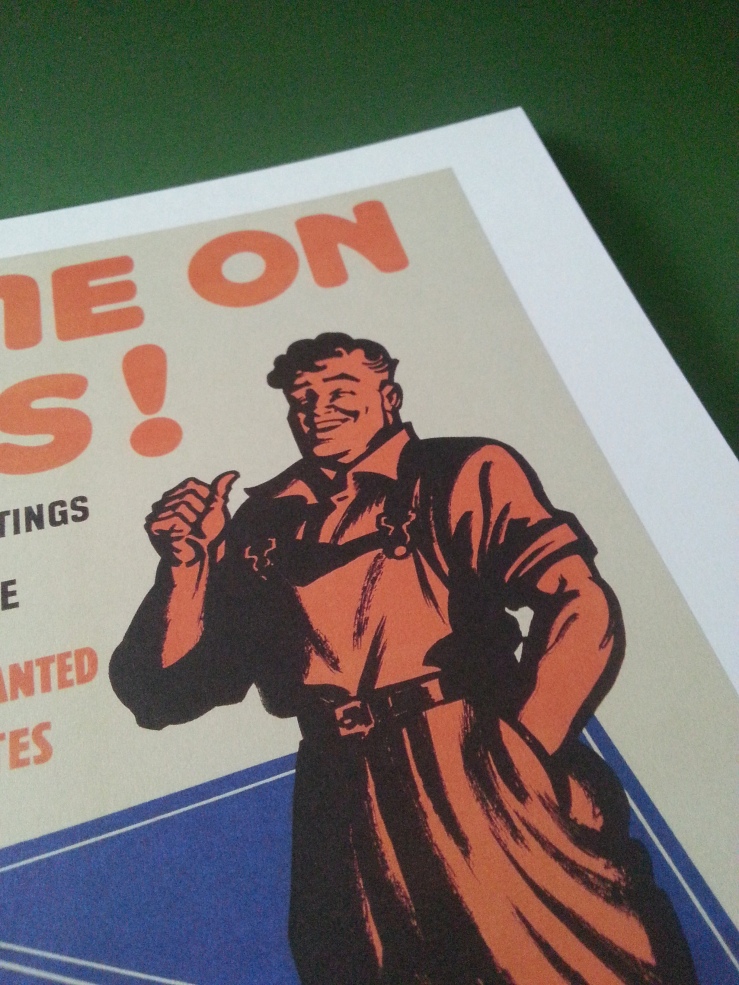

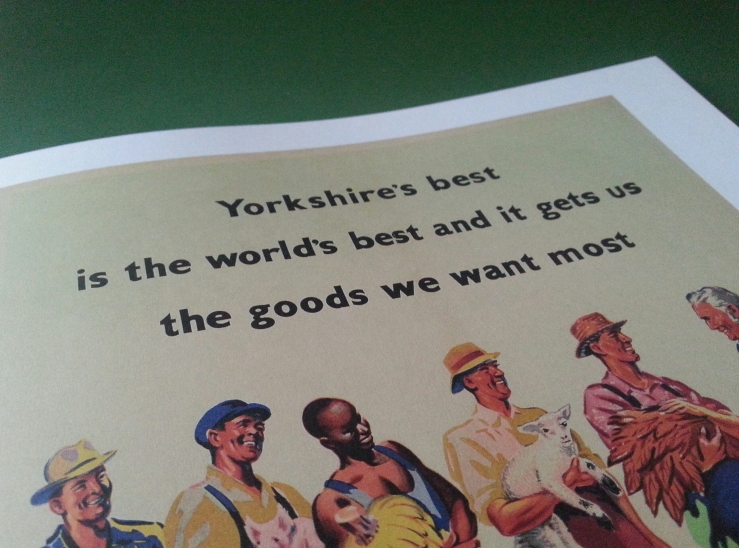

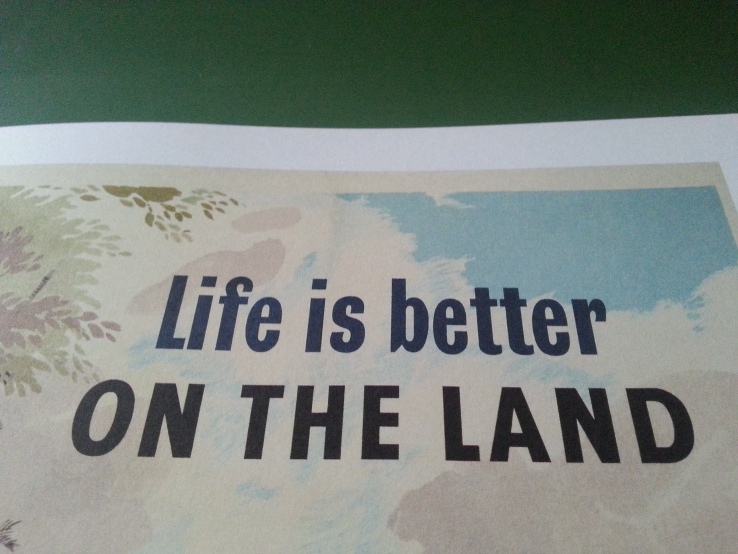

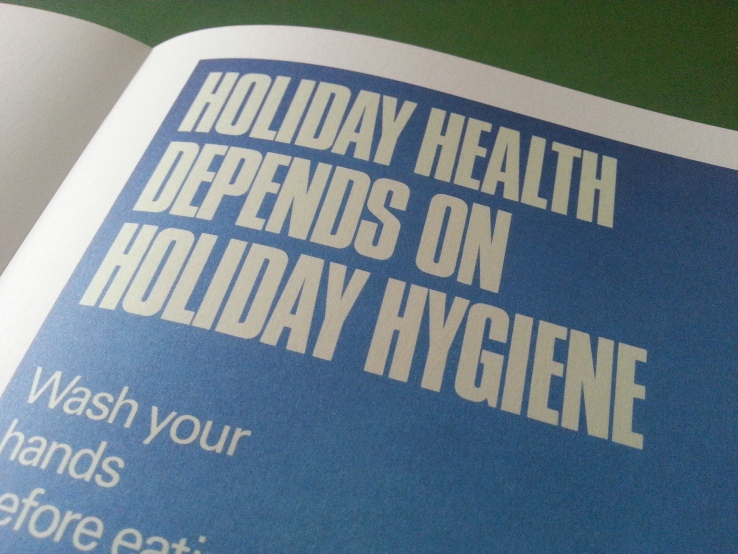

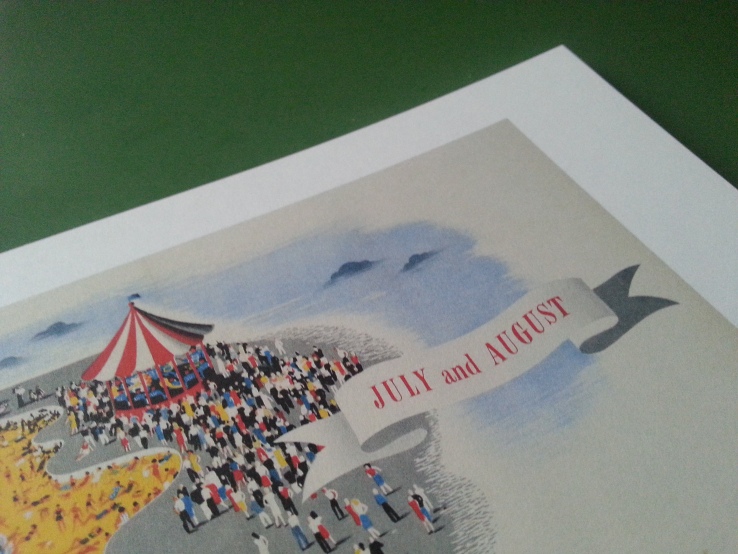

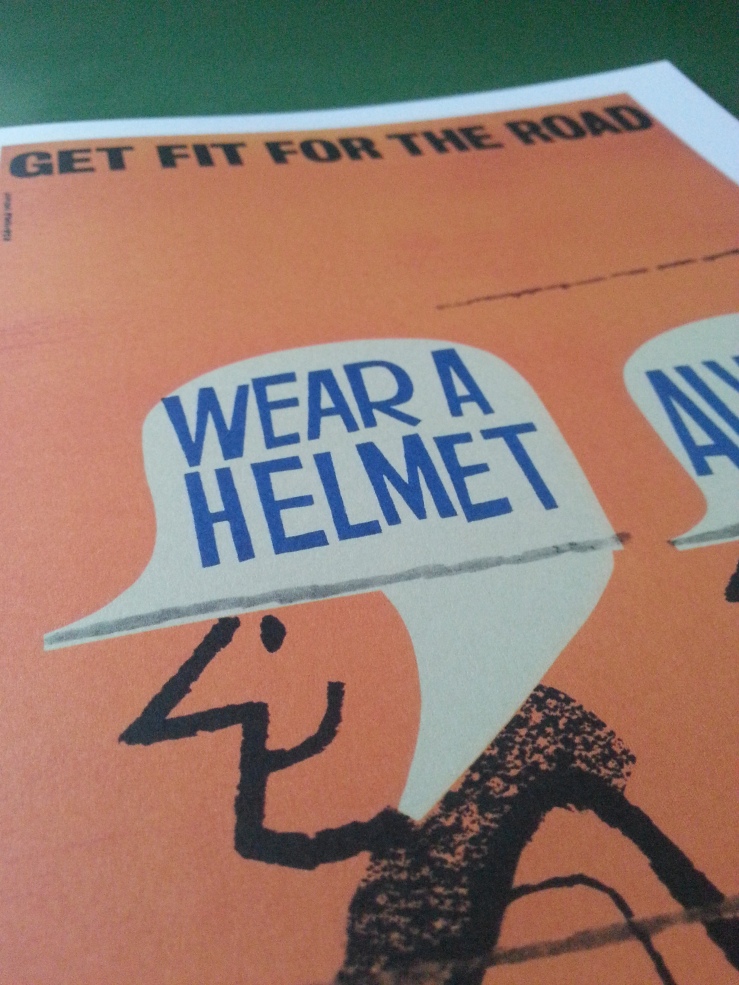

As an artist, my work has – at least recently – become about the marriage of type and design to spread a message. So this book, of posters sorted from The National Archives, is inspirational.

Over 40 posters can be pulled out and stuck on the pinboard; you can literally surround yourself with illustration, typography and design.

A useful resource for designers, social artists and marketeers – but also essential for anyone who loves vintage and retro design.

I’ve always liked badges – my childhood is defined by a Shaftesbury Playhouse badge from a holiday, a Clark’s Commando badge given with new shoes, a Warlord badge for being one of Peter Flint‘s secret agents, a Tufty Club road safety badge. The best bands gave me badges, too – Blur gave me an enamelled Mallard steam train when I crewed for them circa Modern Life Is Rubbish, Spitfire‘s liberated World of Sport logo was like a shibboleth amongst indie musicians, S*M*A*S*H‘s new wave aesthetic was complemented by the badge on the jacket.

So the first bit of serious kit Revolutionary Arts acquired was a badge machine, and since then many projects have been marked with a badge.

Badges, clockwise from top left:

Bedford Happy: round 38mm badges for distribution at workshops, and square badges to mark participation in (for example) the mail art call.

Made in Worthing: an arts festival, commissioning new work for the town, which ran for three years.

Dreamland Margate: Limited edition pair of badges for the first hundred people at an open afternoon on the derelict site.

We Will gather Cashmob; the online volunteering platform was used to boost the cashmob craze, where a mob of people turn up at a local shop armed with a fiver to spend. Badges distributed at more than a dozen events around the UK.

I’m a Dreamland Volunteer: large handmade badges for volunteers at the Dreamland open afternoon, to mark volunteers – an edition of 40.

#KYOKent: an unfolding mystery, inspired by a locked trunk found in a Margate junk shop.

I’m currently working on more designs for Bedford Happy, and a limited edition four-badge pack of designs inspired by some of my favourite places in Margate.

Originally written for the Worthing Community website – this comprehensive Tank Girl biog was the site’s most popular page, so when that site was lost I moved it to my old blog, I Hate Dan Thompson, where it’s had 37,695 views. Woo.

“It’s just a matter of trawling our brains for good ideas” Jamie Hewlett

In 1988, artists Jamie Hewlett and Alan Martin created Tank Girl for Issue One of Deadline Magazine. The pair, living in a Worthing bedsit, could have had little idea of where she would take them. While studying at Northbrook College of Art and Design, Hewlett, Martin and fellow student Philip Bond, had created a fanzine called Atomtan. Deadline, created by Steve Dillon and Brett Ewins, was a more accomplished forum for these new talents. Even amongst strips like Wired World, the great Love And Rockets and Hewlett and Martin’s own Fireball XL5, Tank Girl, with its post-feminist and post-apocalyptic vision of a not-too-distant future, stood out.

Seminal style magazine The Face referred to her as “Fab!” while the NME predicated “a rise to world domination”. The anarchic comic strips were full of cut-and-paste imagery, and used a visual equivalent of the sampling that was becoming so popular in a music scene where guitar bands like Pop Will Eat Itself, Jesus Jones and Carter USM were discovering new technology.

It was easy, in the politicised late-’80s and early ’90s, to identify with Tank Girl’s aggressive attitude, upfront humour and sexuality. Hewlett and Martin said “She was Thelma and Louise before the fact; she was Mad Max designed by Vivienne Westwood; Action Man designed by Jean-Paul Gaultier.” She was an obvious icon, and Tank Girl t-shirts began to spring up- including one for the Clause 28 March, against Thatcher’s homophobic legislation. In 1991, Deadline was approached by Wrangler, who, keen to build an advertising campaign for their jeans that was individual and anarchic, used Tank Girl in a series of press ads in 1991. Hewlett and Martin subverted the character at every turn. She flirted with a hippy revival and new age fashion before it was fashionable, dabbled in post-modernism, and hung out with riot girrrls and the beat generation. Tank Girl could be all things to all people and Hewlett and Martin revelled in their artistic freedom.

More surprisingly, readers loved this freedom too. Far from wanting Tank Girl to be tied down to shooting, shouting and spitting, they wanted to see what Hewlett and Martin could dream up next.

Tank Girl wasn’t just a British phenomena, though. Penguin, the largest publisher in Britain, had bought the rights to collect the Tank Girl strips as a book (they all appeared first in Deadline), and offers for foreign rights were plentiful. Before long, Tank Girl had been published in Spain, Italy, Germany, Scandinavia, Argentina, Brazil and Japan; several publishers were fighting for the US license. Eventually, Dark Horse Comics acquired the US rights to publish Tank Girl and a US version of Deadline. Two successful series of Tank Girl’s adventures and two collections created a stir in the US, and before long there was interest in a film version.

Established rock stars including Adam Ant, Billy Bragg, The Ramones and New Order loved her and were keen to be involved in the magazine. In the early ’90s, bands like Blur, The Senseless Things, Carter USM, Curve and Teenage Fanclub all appeared in Deadline. In true post-modern style, comic strip and reality blurred. Many of the bands appeared in the strips and Hewlett’s artwork appeared on their record sleeves. Sarah Stockbridge, a catwalk model and favourite of punk designer Vivienne Westwood’s, brought Tank Girl to life in a series of photos that went on to be used in Elle, Time Out, Select and The Face. Vogue, too, featured Tank Girl. They cited her as a crucial influence on “Bad Girl Fashion” which featured shaven heads, body piercing and tattoos.

Rachel Talalay, producer of Hairspray and Cry Baby for cult director John Waters, and herself director of Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare, called up Deadline’s Tom Astor. Talalay had been sent the Tank Girl book for Christmas and was immediately smitten. With an unswerving belief in the project, she steered the Tank Girl movie into pre-production with MGM in January 1994.

Hewlett, although still living in Worthing with girlfriend and one-time Elastica member Jane Olliver, was spending time with fellow Deadline artist Glynn Dillon, hanging out with bands in Camden’s Good Mixer pub and helping formulate a scene that would become Britpop. Hewlett and Dillon brought their new friends to Worthing, and to seafront venue The Wine Lodge. The pub was described by press as ” Camden on Sea.” Elastica, Menswear and Blur could be seen listening to DJs like Worthy Dan, who went on to work at legendary London club Blow Up, whose website http://www.blowup.co.uk charts their long-running success. After the Wine Lodge, the party carried on at The Factory, a nightclub whose design- by Hewlett, and friends including fellow artist Philip Bond- echoed the Tank Girl strip. Bold red and green stripes, a wall of blown-up panels from Tank Girl set against ’70s wallpaper, a Ford Escort hung from the ceiling and toilets pasted with pages from old annuals were a suitable backdrop for a mix of alternative sounds. [Hewlett’s nightclub designs were eventually lost when I redesigned the club. DT]

Meanwhile, the Tank Girl film was ready for the cinemas. Disappointingly, the final film was a result of much fighting, some agreement, and too much compromise. Although it preserves the anarchic and nonsensical charm of the Tank Girl strips, reeling from Busby Berkley to Mad Max and back through Tex Avery, it mystified critics and public alike. It sacrificed the danger and raw vitality of the original, and was a box office flop. Deadline, after reputedly taking huge gambles on their future with Tank Girl merchandising, folded.

A new Tank Girl comic was short-lived. Meanwhile, Hewlett and Olliver opened a vintage clothes shop in Worthing. Called 49, it, too, folded after a short life. It looked like Hewlett and Martin’s fifteen minutes of fame was over. Hewlett moved to London. After splitting with girlfriend Olliver, he moved into a flat with Blur’s Damon Albarn. He had also just split from his long-term girlfriend, Elastica’s Justine Frischmann.

Hewlett worked on a number of advertising campaigns. His designs also appeared on the set of children’s TV programme SM:TV, presented by ex-pop stars and Byker Grove actors Ant and Dec.

Rumours about how Albarn and Hewlett spent their time were rife, but no-one predicted the end result of their relationship – Gorillaz. The band are four comic characters who could easily have appeared in a Tank Girl strip. Using digital technology, Hewlett has animated his characters, giving a new twist to his distinctive visual style. Interestingly the band’s live line-up includes The Senseless Thing’s drummer Cass. The website, http://www.gorillaz.com is a testament to Hewlett’s creativity. And with Gorillaz winning MTV Music Awards including Best Dance Track and Best Song, Hewlett has taken the earlier crossover of comics and real life to new extremes.